Biospeleology

More than 500 subterranean taxa are known in Croatia and 50% are endemic. Many are relicts of fauna from deep in the geological past.

Biospeleology is a scientific branch that studies subterranean animals, their habitats and their mutual relationships. The name comes from three words of Greek origin: bios, meaning life, speleos, meaning cavity, and logos, meaning science. This is a synthesis of sciences that bring together two fundamental scientific disciplines: biology and speleology.

Biospeleologists are scientists and researchers that enter into caves and pits in search of subterranean animals, who collect and photograph these animals, and then in the laboratory determine which species they have found and study them in great detail. When a previously unknown species is found, the animal is described in detail, given a scientific name, and this is published in a scientific journal to make this information about the new find available to all.

The word biospeleology was first used by Armand Vire of France in his publication La Biospeologie published in Paris in 1904. In it, he described the science which researches the living creatures that inhabit the underground.

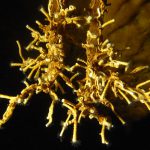

Speleological structures are inhabited by animals that are partly or completely adapted to the demanding conditions of life underground, such as a lack of light, scarcity of food, and very high air humidity. These animals live, or only visit, these habitats for various reasons, from taking shelter from unfavourable conditions on the surface, hibernation, or reproduction.

Until 1832, when the narrow-necked blind cave beetle Leptodirus hochenwartii was discovered in the Postojna Cave in Slovenia, it was believed that cave habitats did not contain life. This discovery stimulated new research of underground habitats, especially caves. To date, more than 7500 subterranean taxa (species and subspecies) have been described in the world, with some 1200 of these found in the Dinarides Mountain range. More than 500 subterranean taxa are known in Croatia, nearly 7% of the total number of global species. More than 50% of subterranean taxa are endemic. Many are relicts of fauna from deep in the geological past. The cave habitats of numerous species are dominated by the beetles, followed by crustaceans, molluscs, pseudoscorpions, spiders and centipedes. These groups account for nearly 90% of all known cave taxa.

In addition to the many species found in Croatia, the country also has certain unique representatives of the subterranean fauna, such as the only known freshwater cave sponge, the Ogulin cave sponge Eunapius subterraneus, the only known freshwater subterranean bivalve mollusc, the Dinaric cave bivalve Congeria kusceri, the only European freshwater subterranean vertebrate (amphibian), the olm Proteus anguinus, the only subterranean freshwater cnidarian Velkovrhia aenigmatica, the only subterranean freshwater arthropod, the Dinaric cave-dwelling tube worm Marifugia cavatica, and the only flying troglobiont in the world, the orthoclad Troglocladius hajdi.

The lack of study of speleological structures in the area of Krka National Park is the main reason for the relatively late start of biospeleological research here. It was not until the 1960s that Slovenian biospeleologists made the first important discovery of subterranean fauna in the present day area of Krka National Park: they described the subspecies of the cave-bug Monolistra pretneri spinulosa (Cave near the mill at Miljacki – Miljacka IV), the order of the stygobiont snail Dalmatella with the type species D. sketi, and the species of stygobiont snail Lanzaia skradinensis (karst spring near Skradinski Buk). The first comprehensive biospeleological research in the broader area of Krka National Park was conducted in 1989 and 1998 by the staff of the Croatian Natural History Museum. The Croatian Biospeleological Society, in cooperation with the Public Institute of Krka National Park, conducted an inventory of the cave fauna in 2005 and 2010, and in 2013 conducted research of rare and new cave taxa. Throughout the park area, speleological and biospeleological research is ongoing, in addition to monitoring of bat nurseries and olm populations.

Photo: Branko Jalžić