The Amphitheatre in Burnum and the importance of amphitheatres in the Roman Empire

Amphitheatres represent one of the best preserved examples of ancient Roman architecture. Many are still in use today, hosting various events, from re-enactments of gladiatorial fights to musical concerts and theatre performances

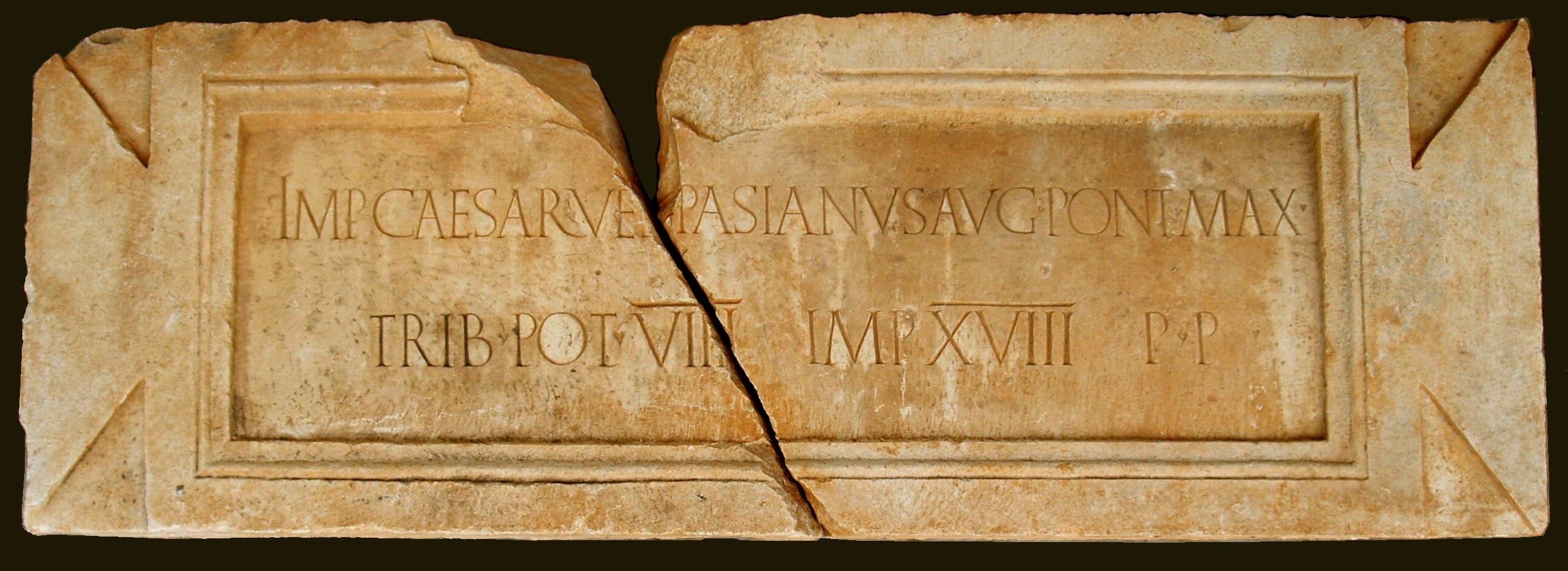

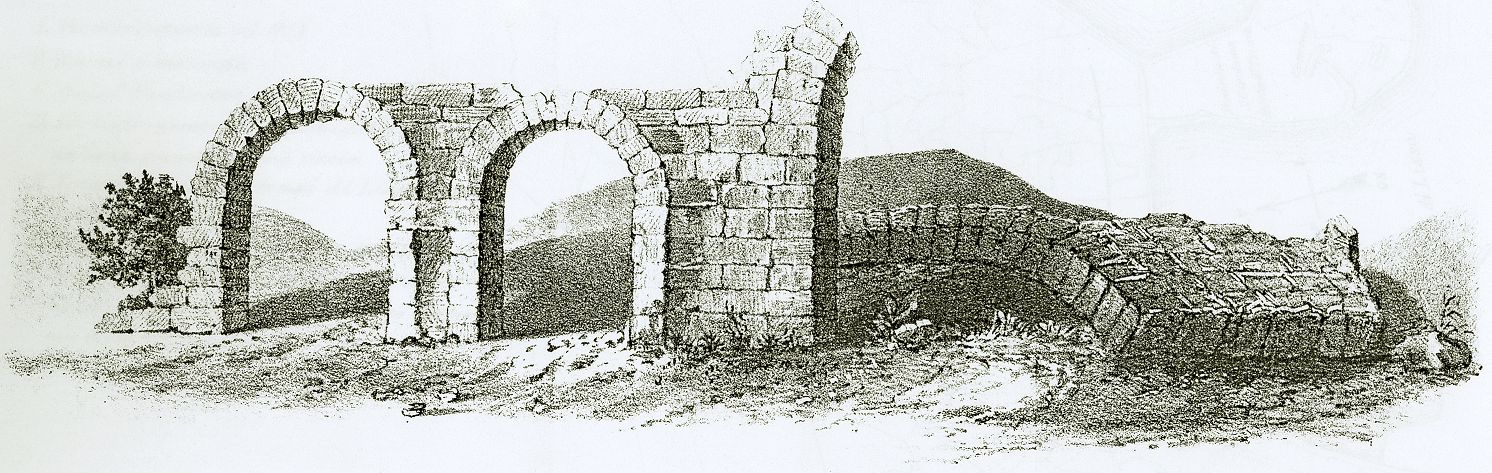

A military amphitheatre was built on the southwestern periphery of the Roman military camp complex at Burnum. The amphitheatre in Burnum belonged typologically to the type with four entrances – two main ones at the top of the ellipse, and two side ones. It was constructed on top of an adapted natural sinkhole. Several building phases of adaptation were noted during archaeological excavations. It acquired its final form in AD 76/77, when an inscription with the name of the emperor Vespasian was immured on the facade of the southern entrance, which marked the completion of construction or rather reconstruction. On the basis of solid evidence, it was established that the Burnum amphitheatre had been built earlier, i.e. that the construction, probably during the reign of the Emperor Claudius, was started by members of the XIth legion, who completed all the necessary preliminary work in terms of the preparation and levelling of the terrain and then built the amphitheatre. During the residency of legionary and auxiliary units in Burnum, the amphitheatre served the needs of the army, but after AD 86, after the IVth legion left the camp, it was definitely also used for civilian purposes. It is not known how long the amphitheatre at Burnum served its function, but it is evident that it collapsed over time due to dilapidation.

What are amphitheatres? Amphitheatres are free-standing open structures of circular or more often oval shape with a central space for the presentation of events (arena), surrounded by rows of seats for spectators. The term amphitheatre is composed from two words, coming from the Greek amphitheatron “double theatre” (amphi “around”, “two-sided” + theatron “theatre”; Lat. amphitheatrum). The architectural form of the amphitheatre is of Italic or Etruscan-Campanian origin and reflects the requirements of specific forms of entertainment (performances) preferred by the inhabitants of southern Italy. Originally, such entertainments were held in the forum, and occasionally wooden bleachers would be erected for spectators. The earliest permanent amphitheatre is the one in Pompeii (around 75 BC), known as the spectacula, measuring 136 x 104 m, which could accommodate around 20,000 spectators. The first amphitheatres, with wooden seats, were built on stone and earthen slopes. Thanks to the army, amphitheatres of all sizes were built throughout the Empire, most often by military camps, in this manner spreading Roman culture. They were used for entertainment, but also for training soldiers.

The central part of the amphitheatre is the arena (meaning “sand” in Latin). Depending on the size of the amphitheatre or the place where it was built, the arenas (fighting grounds) could be simple flat surfaces or complex underground labyrinths. The labyrinths consisted of areas for lifts and machines that lifted stages and animals to the surface of the arena and the gladiator quarters. Around the arena, separated from it by a high wall, were raised seats for spectators. The rows of seats were separated by gates that controlled access to the arena and isolated it from the public. In the lowest section, i.e. on a podium, the emperor and his entourage sat in a separate loggia. On the opposite side of the arena, also on a podium, sat vestal priestesses, consuls, praetors, priests, and other distinguished guests. Senators and high-ranking military dignitaries sat in the remainder of the first gallery. The second gallery was reserved for the patricians, the third for the plebeians, and the fourth, and last, for the women who sat in the boxes. A canopy (velum) or velarium was raised by sailors to protect the spectators from the sun. Each of these galleries was divided into wedge-shaped sections (cunei) by radial corridors leading to the exits (vomitoria).

Amphitheatres represent one of the best preserved examples of ancient Roman architecture. Many are still in use today, hosting various events, from re-enactments of gladiatorial fights to musical concerts and theatre performances.

The Romans loved spectacles, which were an opportunity to escape from everyday reality. In amphitheatres, ordinary people could watch extraordinary performances that stimulated the senses and inflamed emotions, such as gladiatorial games, staged naval battles, wild animal hunts, and public executions. The rulers knew this quite well, so in order to increase their popularity and reputation among the people, they organized lavish and spectacular performances that cost a considerable amount and lasted for several days. A large number of people were employed at such shows, from animal tamers, hunters, and musicians to sand rakers and the like.

The first Roman emperor, Octavian Augustus, established the seating rules in amphitheatres. The first rows, with the more comfortable seats, were reserved for the upper social class. The reserved seats were engraved with the numbers or names of those who reserved them. The tickets were probably free.

Executions of criminals were also held in amphitheatres, usually during lunchtime. The methods of execution were very ingenious and cruel, for example, attacks of wild animals on the convicts (damnatio ad bestias) or forcing them to fight against well-armed and trained gladiators or against one another, burning at the stake, crucifixion, etc. The spectators did not watch it passively, on the contrary, sometimes executions were called off if the public demanded it.

Two hundred and thirty amphitheatres are known on the former territory of the Roman Empire. Their special shape, function, and name differentiate them from Roman theatres, hippodromes, and stadiums. After gladiatorial games were abolished in AD 404, most of the amphitheatres fell into decay. Their architecture was largely dismantled, so they became in fact quarries for worked stone. Some were demolished, others turned into fortresses. Only a few survived more or less in their original form, and even churches were built inside some of them.